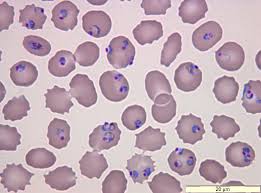

Malaria is a disease resulting from infection by parasites of the Plasmodium species, a sporozoan usually transmitted to humans by the infected female Anopheles mosquito.

Commonly four species. ie P.falciparum, P.vivax, P.ovale and P.malariae are responsible for the disease.

About 20 species of Plasmodium affecting non-human primates may occasionally cause disease in humans. In recent years, one simian species –P.knowlesi – has been frequently identified in humans, mainly in S.E.Asia.

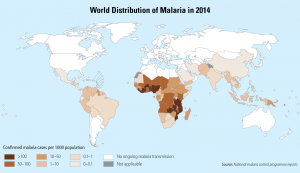

About 4 billion people, throughout the world, are susceptible to malaria. There are about 500,000 severe cases each year and about 12,000 die.

Biology

The infection is acquired through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito, when the malarial parasite is injected into the blood stream and begins its life cycle. Humans are the only reservoir of human malaria and bites from the Anopheles mosquito occur mainly between sunset and sunrise.

The disease can be spread through blood transfusion or through the sharing of needles. Untreated or inadequately treated patients may be a source of infection for more than three years.

Incubation period

The period between the bite and the appearance of parasites in the blood varies between 6 and 16 days, depending to the species involved. Symptoms may not occur at that time and may be delayed for weeks or months. (Suboptimal suppression with prophylactic drugs may delay the clinical presentation.)

Symptoms

Although features vary, many will experience malaise, fever, shaking chills, sweating, headache, muscle pain and weakness, cough, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Early malaria is sometimes mistaken for an episode of influenza, often with tragic consequences.

One form of malaria, namely P.falciparum malaria, usually produces more severe symptoms.

Travellers

For travellers, risk varies from country to country and in some the risk in urban areas is low. However, this is not the case with Africa and India, where urban transmission occurs.

Global areas of risk of malaria per month of travel (from highest to lowest) are as follows: Papua New Guinea / Irian Jaya, Africa, South Asia, Micronesia, South-East Asia, South America and Central America. Many areas visited by tourists have an extremely low risk such as central Thailand (approximately 1/35,000) and that the mortality rate from malaria for travellers in Africa is approximately 1/300,000.

There has been little reduction in the worldwide incidence of malaria. We are witnessing increasing levels of transmission and a return of malaria to areas from which it was previously eradicated. Resistance to insecticides is now widespread and resistance to antimalarial drugs is increasing.

Vaccine Information.

The first licensed vaccine against malaria (Mosquirix GSK) has been approved by the European Medicines Agency’s [EMA] Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) for use outside the European Union. It is intended for use in children between 6 weeks and 17 months providing protection against P.falciparum and also against hepatitis B. It does not provide complete protection (up to 56% protection in children aged 5-17 months) and this declines with time.

The vaccine will not be available for travellers, and the price has not been disclosed.

Queensland researchers believe they could be the first to find an effective vaccine for malaria; hopefully against all strains of malaria.

The Management of Malaria

Until an effective vaccine is readily available, the World Health Organisation recommends a four point (A,B,C and D) approach.

A – Be Aware of the risk

Before travelling to Papua New Guinea / Irian Jaya, Africa, South Asia, Micronesia, South-East Asia, South America and Central America, discuss with your travel health doctor, the expected risk. This will vary with your actual itinerary, your accommodation, the duration of your trip and the season of travel.

Learn about malaria, its incubation period and symptoms and any special considerations applying to your destination.

Remember: malaria may present many months after returning from a malarial area. Always treat an unexplained fever as possible malaria. Consult your doctor if worried.

B – Avoid being Bitten by mosquitoes

Malaria is a disease acquired through the bite of an infected mosquito and avoiding bites is the mainstay of prevention. Mosquitos, which carry the malarial parasite usually, bite between dusk and dawn and are kept away by various techniques:

1. Insect repellents, usually containing DEET (eg Repel, RID or Aerogard in tropical strength). Avoid high concentrations in children and do not apply to eyes or mucous membranes, or to sunburnt or damaged skin. Repellents may need to be applied 3-4 times/day.

2. Mosquito coils containing synthetic pyrethroid may be used in certain accommodation types. Knock down aerosol sprays are very effective but too cumbersome for many travellers.

3. Always wear long, loose, light coloured clothing, covering as much as is practicable. (Do not wear dark clothing or use deodorants, perfumes or after shave.) Clothing soaked in permethrin (eg The Dip) offers added protection against mosquitoes and other insects.

4. Sleep in mosquito nets impregnated with permethrin. If possible sleep in well screened rooms. The insecticide impregnated bed net roughly reduces the risk of malaria in endemic areas by 50 percent if used correctly. Impregnated bed nets will probably continue to be the main tool for malaria prevention and control in endemic areas.

C – Chemoprophylaxis

Take anti-malarial medications in order to prevent infection.

No anti-malarial prophylactic medication guarantees protection against malaria. However, prophylactic medications greatly reduce the risk of disease.

Your doctor will prescribe medications (usually one of doxycycline, mefloquine or Malarone), depending on your itinerary and personal requirements. Kodatef (tafenoquine succinate) is a new weekly oral antimalarial recently approved by the TGA.

Some medications are ineffective in certain situations, others are too dangerous (eg in pregnancy), some are very expensive – especially for long stay trips – and each drug may be unsuitable for some people.

Chemoprophylaxis should be:

– taken as prescribed

– taken with food and swallowed with plenty of water

– continued (except for Malarone) for four weeks after leaving the malarial area.

D – Early Diagnosis and treatment

The treatment of malaria when diagnosed by an individual in a remote location is very different from that in which the patient has full medical and hospital care readily at hand.

The essence of good care in either situation is early diagnosis. Remember: If a fever develops one week or more of entering a malarial area, assume the presence of malaria and seek urgent medical attention.

In the first instance ‘stand-by emergency treatment’ (SBET) requires ‘on the spot’ diagnostic skills and a good understanding of the drugs to be used. This routine is sometimes used where medical care is not available and the medications used will depend on the location and knowledge of the patient.

The actual treatment of malaria will depend on the circumstances (mild illness or severe/ complicated disease) and may involve hospital care and a variety of drugs additional to those mentioned above for the prophylaxis of malaria.