The Disease

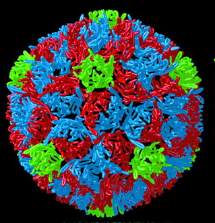

The highly contagious poliovirus (of which there are three major wild poliovirus [WPVs] types – P1, P2, and P3) is spread by contamination from the faeces or saliva of infected people. The virus enters the body through the mouth and multiplies in the intestines.

Similarly, the live viruses in Sabin vaccine (known as vaccine-derived polioviruses [VDPVs]) can produce polio outbreaks in areas of low vaccine coverage. (See below.)

Incubation period1-2 weeks.

Features

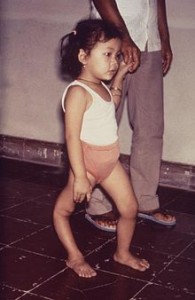

The infection causes fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. This may progress to severe muscle pain and stiffness of neck and back, followed by paralysis. About 80% experience spinal paralysis and, of these, between 2 and 30% will die. Some 1 in 20 hospitalised patients die and 1 in 2 surviving patients are permanently paralysed.

Post-polio Syndrome

Some patients develop new symptoms of weakness, joint and muscle pain and fatigue, many years after the initial infection. About 20-40% of people who have had polio will develop ‘post-polio syndrome’. Re-innervating nerves, developed after the original infection, are thought to break down with time.

Former Senator Dr John Tierney, OAM, is Australia’s most distinguished and best known polio sufferer.

Background

Large polio epidemics caused panic every summer during the 1940s and 50s in industrialised countries. At that time, people with polio affecting the respiratory muscles were immobilised inside iron lungs – huge metal cylinders that operated like a pair of bellows to regulate their breathing and keep them alive.

The peak incidence of polio in Australia was in 1938 and the last case was reported in 1978.

The Americas were declared polio free in 1994 and the Western Pacific, including Australia, in 2000.

Wars

Polio is often found to be high in areas with high levels of conflict and instability and wars have resulted in the reappearance of polio in countries that have been polio-free for decades. Conflict, political instability, hard-to-reach populations, and poor infrastructure continue to pose challenges to eradicating polio; each country has a unique set of challenges, which require local solutions.

From around the world:

Since the 1988 World Health Assembly resolution to eradicate poliomyelitis, the number of countries where polio is endemic has decreased from 125 in 1988 to six at the end of 2003.

In July 2007, a Pakistani student was found to have polio in Melbourne. He had returned from a holiday in Pakistan where he first noticed symptoms and became the first case reported in Australia since 1986.

Global polio eradication programs have been part of international public health efforts since the 1980s. Now, only two countries (Pakistan and Afghanistan) are polio-endemic, meaning that the disease regularly circulates in those areas.

By August 2015, Africa achieved a major milestone – no polio cases in a year. The last polio case on the continent was reported in Somalia in August 2014. Nigeria has also played a big role in combatting polio. Thanks to aggressive vaccination campaigns, Nigeria celebrated one year without a case of polio in July 2015 and was removed from the list of polio-endemic countries. Unfortunately, two children were paralysed with polio in August 2016. Countries can be declared polio-free three years after the last reported case.

Advice for travellers

In recent years, wild polio virus has been reported from: Africa: Angola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Sudan and Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Yemen.

Only two polio-endemic countries remain – Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Hajj requirements: All pilgrims under the age of 15 will receive OPV on arrival. Travellers from Afghanistan, India, Nigeria, Pakistan and Sudan will also receive OPV on entry to Saudi Arabia.

Travellers should ensure adequate protection and discuss immunisation with their doctors.

More information about polio and other infectious diseases may be accessed at smartraveller.gov.au.

Vaccine Information.

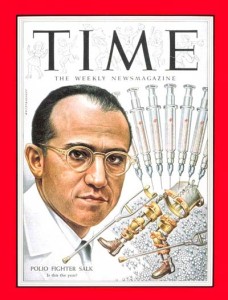

An inactivated (killed) injectable vaccine (IPV) was developed in 1955 and a live attenuated (weakened) oral polio vaccine (OPV) followed in 1961.

The vaccines effective against polio are

(1) a live attenuated virus vaccine, OPV (Sabin), given orally and

(2) an inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine, IPV (IPOL), is given by injection.

OPV has been used in Australia since 1960 but was replaced by IPV (IPOL) in 2005.

Commonly IPOL is used in combination with other vaccines such as Boostrix-IPV, Infanrix Hexa, Infanrix–IPV, Infanrix Penta, Pediacel, Poliacel and Quadracel, (see also ‘Diphtheria’) which are now part of the national immunisation schedule. Infanrix-IPV is the combination vaccine commonly used in Victoria.

IPOL is available as a stand-alone vaccine and is used mainly in travellers to countries where polio is endemic.

Problems associated with OPV

Less than 1% of OPV recipients develop diarrhoea, headache, and/or muscle pains. However, the live virus is excreted for up to six weeks after dosing and about 1 in 2.4 million recipients, or their close contacts, develops vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP). Two cases have occurred in Australia in the past 30 years (1986 and 1995). It is for this reason, that OPV use in Australia ceased in 2005 and was replaced by IPV. While OPV continues to be used in other countries, immunosuppressed individuals and their close contacts should be vaccinated with IPV. Courses started with OPV may be completed with IVP.

The earliest attempts to produce a polio vaccine were surrounded by controversy, however, April 12, 2005, marked the 50th anniversary of the announcement that a safe, potent, and effective vaccine against polio had been found by Dr. Jonas Salk and other colleagues.

An account of significant events in polio immunisation in Australia is available at the NCIRS site.