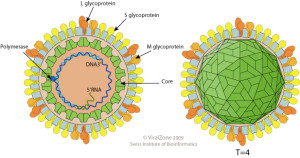

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus belonging to the hepadnaviridae family. The outer surface of the virus is glycolipid, which contains the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Other important antigenic components are the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg).

Most young children and up to 12% of adults who catch the virus become “carriers” and can continue to spread it to other people. These carriers are also at an increased risk of developing liver disease and cancer later in life.

Transmission

The HBV virus is spread via the blood or sweat of an infected person, usually through sexual contact or from the unsafe use of injected drugs. Spread may also occur from mother to child at birth, but also in a variety of other ways.

Incubation

The incubation period ranges from 45-180 days, with an average of 60-90 days.

Features

Approximately 6o% of people with acute hepatitis B will have no symptoms. The onset of illness, when it occurs, is usually insidious with anorexia, vague abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting and sometimes arthralgia and rash, often progressing to jaundice. Symptoms and jaundice usually disappear after 1-3 months and abnormal liver function tests may return to normal after 1-4 months.

Complications

The principal cause of morbidity and mortality from hepatitis B is chronic infection, which may occur irrespective of symptoms. Chronic infection can lead to cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocellular cancer, usually over a prolonged period. The risk of chronic infection is greatest in those infected as infants (90%), particularly if infected in the perinatal period. Accordingly, preventive efforts have been focussed, in both the indigenous and non-indigenous community in Australia, on preventing maternal-infant transmission. Infections acquired in adulthood may become chronic in <5% of patients.

Diagnosis

Acute HBV infection is diagnosed by the detection of HBsAg or of HBV DNA together with an elevated ALT and high levels of IgM HBcAg, in serum. Chronic carriers are those in whom the HBsAg persists for more than six months.

Notification

Hepatitis B infection must be notified in writing within five days of diagnosis.

Progression

Untreated, 25% of people infected with hepatitis B will develop cirrhosis and 5-10% will develop liver cancer. Every year, 4 or 5 die from hepatitis B infection, however about 200 die each year from liver cancer.

School exclusion

Children with hepatitis B are not excluded from school.

In Victoria, hepatitis B is a Group B notifiable disease and must be reported within 5 days.

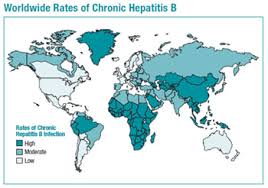

Between 240 and 350 million people are estimated to be living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and over 2 billion have been infected.

About 200,000 Australians carry the virus, ie 0.8% of the population and the numbers are growing, despite the routine use of vaccines in children since 1998. About half of those infected were born in the Asia-Pacific, North Africa, Mediterranean or Middle Eastern regions, while 16% are indigenous Australians.

Over 100,000 Australians regularly inject drugs and the majority of those with hepatitis B infection also have hepatitis C. The interest of governments in this group and in others with hepatitis B, despite the potential costs to the health system, is close to zero.

The incidence of hepatitis B in ethnic groups in Australia is unknown.

Terminology

HBV – Hepatitis B virus

HBsAg – Hepatitis B surface antigen

HBeAg – Hepatitis Be antigen; indicates viral replication

HBcAg – Hepatitis B core antigen

Anti-HBs – Antibody to HBsAg (Indicates past infection or immune response to HBV vaccine

Anti-HBe – Antibody to HBeAg suggests possible carrier state

Anti-HBc – Antibody to HBcAg, indicating past infection with HBV

IgM anti-HBc – Antibody to HBcAg, indicating recent infection with HBV; positive 4-6 months after infection.

Hepatitis B is a vaccine preventable disease

Around the world, about 400 million people live with chronic hepatitis B and 2-4 million people die from hepatitis B-related disease each year. It is a major concern in third world countries and vaccination is commonly recommended for travellers to these areas.

As an example, Indonesia is estimated to have 13 million sufferers nationwide and one in every 20 residents of Jakarta is infected with the virus.

The incidence of hepatitis B in some Asian countries is estimated at: China 15%, Hong Kong 8.8%, Taiwan 15-20%, Philippines 12%, Fiji 10-20%, India 3.3%, Malaysia 5.2% and South Korea 2.8%.

Vaccine Information.

The modern hepatitis B vaccines are built around non-infectious recombinant DNA. Vaccination is recommended for all unvaccinated adults at risk of infection, but the presence of a specific risk factor is not a necessary prerequisite for vaccination.

Vaccines available in Australia

All formulations are made from a recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine and all may contain yeast proteins.

Monovalent vaccines

Engerix-B and Engerix-B Paediatric (GSK) and

H-B-Vax II and H-B-Vax Paediatric (CSL/Merck)

Combination vaccines

Hepatitis vaccine is now most commonly given in combination with others.

1. Infanrix hexa

Hepatitis B with tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis, inactivated polio (type 1) and Haemophilus influenzæ type B.

2. Twinrix and Twinrix Junior (GSK)

Hepatitis B and inactivated hepatitis A in a pre-filled single syringe.

Usually three doses of hepatitis B vaccine are required to provide full protection. In Australia, all newborn babies are now offered a course of four injections during their first 12 months. Older children are provided with a course of two injections in year seven of high school.

Of healthy adults, 5-10% fail to show an adequate antibody response to the hepatitis B vaccine. Perhaps some develop specific cellular immune responses, but most will benefit from a course of intradermal vaccination (0.25ml ID each fortnight, for 4 doses).

The babies of infected mothers should receive the vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin at the time of delivery.

Premature babies (Hepatitis B immunisation is especially advised if the child’s mother is a carrier of hepatitis B and in children who come from communities where there are higher rates of hepatitis B infection).

In those at occupational risk, especially healthcare workers, serological testing is advised three months after completing the course.

There is no connection between the hepatitis B vaccine and the subsequent development of chronic fatigue.

New:

Heplisav-B (Hepatitis B Vaccine, Recombinant, Adjuvanted; Dynavax), approved as a 2-dose (1 month apart) regimen for persons aged ≥ 18 years, will be available in the first quarter of 2018 in the US. Data indicate a protection rate of 95% after 2 doses of Heplisav-B compared with 81% after 3 doses (over 6 months) of Engerix-B (Hepatitis B Vaccine, Recombinant, Inactivated; GSK) in healthy persons. Travax News.

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindications to hepatitis B vaccines are:

anaphylaxis following a previous dose of any hepatitis B vaccine

anaphylaxis following any vaccine component.

In particular, hepatitis B vaccines are contraindicated in persons with a history of anaphylaxis to yeast.

Hepatitis B vaccine is not recommended during pregnancy or while breastfeeding, however, the World Health Organisation does not consider these to be contraindications.

Drug treatment

From the New England Journal of Medicine:

A total of five treatments were now approved in the United States: interferon alfa-2b (which had been available for a decade), lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (peg-interferon).

Concerns about HBV therapies involved side effects and drug resistance as well as costs.

Four new drugs – entecavir, emtricitabine, telbivudine and clevudine – are in Phase III trials in the US.

Entacavir (Baraclude) has been approved by the Australian Drug Evaluation Committee for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

The Future

A plant-derived hepatitis B vaccine, produced in genetically modified potatoes, has been successfully tested in the US and may become the first of many cheaply produced vaccines.

History

The breakthrough understanding of hepatitis came in 1963 when Dr Baruch Blumberg discovered an antigen that detected the presence of hepatitis B (HBV) in blood samples.

Dr Blumberg and his team identified an unusual antigen from a blood sample of an Australian Aborigine, which they called the Australia antigen. After further research, this turned out to be the antigen that caused hepatitis B, which was officially recognised in 1967. In 1976, Dr Blumberg was awarded the Noble Prize for Medicine in recognition of his discovery of the hepatitis B virus. He died on 5 April 2011at the age of 85 years.

An account of significant events in hepatitis B immunisation in Australia is provided at the NCIRS site.