The hepatitis A virus (HAV) is highly infectious and causes disease affecting the liver. Spread is by the oral-faecal route from person to person or from contaminated food or water. The disease is caused by infection from the hepatitis A virus and has been called yellow jaundice, epidemic hepatitis, epidemic jaundice, infectious hepatitis and catarrhal jaundice in the past.

The incubation period averages about three-four weeks. Patients are infectious from the latter half of the incubation period but usually cease to be after the first week of jaundice.

Features

Patients with hepatitis A (previously called infectious hepatitis) experience an acute fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea and abdominal discomfort. A few days later they develop yellow eyes and skin (jaundice) and have dark urine.

Most people recover after a month or so, but some may experience several episodes of illness before recovering.

70-200 cases are reported in Victoria each year, about 2 – 3 deaths are reported in Australia each year.

Hepatitis A does not cause long-term liver disease.

School exclusion

Children with hepatitis A should be excluded from school until a medical certificate of recovery is received, but not less than 7 days after the onset of jaundice or illness.

In Victoria, hepatitis A is a Group B notifiable disease and must be reported within 5 days.

Hepatitis A is a vaccine preventable disease.

Australia

Indigenous Australians

The pattern of hepatitis A shows much higher rates of disease notifications and, importantly, an even greater differential for hospitalisations, in indigenous children aged 0–4 years. By the age of 15 years, this discrepancy has largely disappeared. These data, particularly the high hospitalisation rates in indigenous children, and one death in the most recent 3-year period, contradict the assertion that hepatitis A is always a mild disease in children. In Far North Queensland, routine hepatitis A vaccination of Indigenous children from 18 months of age was introduced in 1999 in response to high numbers of outbreaks, reported deaths and cases of severe disease. That success has prompted the Australian Government to launch a program to immunise indigenous children under the age of five. A course of two injections is given six months apart.

With improving sanitation and living conditions in Australia, the annual notification rate of hepatitis A has declined from 123 notifications per 100,000 population in 1961 to 1 per 100,000 population in 2014.

International

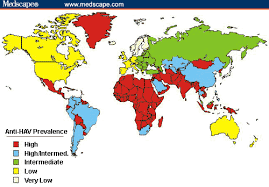

Hepatitis A occurs world wide, mostly in children. It is probably the commonest serious disease acquired by travellers. Significant sporadic outbreaks occur, even in Western nations.

Hepatitis A is much more common in countries with underdeveloped sanitation systems and, thus, is a risk in most of the world. An increased transmission rate is seen in all countries other than the United States, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the countries of Western Europe.

Since the introduction of hepatitis A vaccine, rates of hepatitis A have declined to insignificant levels in most countries of the European Union (EU), but the disease is still prevalent in Bulgaria, Romania, and the Roma population of Slovakia, and travellers should be immunised. In some other Eastern European counties where hygienic conditions are variable and/or public health services are not yet well developed, imported cases of hepatitis A may trigger outbreaks in at-risk groups, which may spread into the general population. Classical endemic countries, such as Egypt, remain a far greater risk to travellers.

Vaccine Information.

The various brands of hepatitis A vaccine (Avaxim, Havrix 1440, Havrix Junior, VAQTA, VAQTA Paediatric) currently in use in Australia are suspensions of the inactivated virus and may be given alone or in combination with hepatitis B vaccine (Twinrix, Twinrix Junior).

Hepatitis A vaccine is also available in combination with typhoid vaccine (Vivaxim).

Hepatitis A vaccine is safe and very effective. The injection may produce some soreness at the injection site, headache and malaise sometimes occurring. Two doses are given, six to 12 months apart and protection extends for many years and is life-long.

Although the manufacturers use slightly different production methods and quantify the HAV antigen content in their respective vaccines differently, the hepatitis A vaccines of the different manufacturers used in ‘equivalent’ schedules can be considered interchangeable, when given in a 2-dose course. Adults previously primed with full-dose adult monovalent HepA vaccine can delay the booster up to 5 years or be given a booster dose of either pediatric monovalent HepA vaccine or adult HepA-HepB vaccine (off-label). Travax UK.

Twinrix

Three doses are required for Twinrix and Twinrix Junior at 0, 1 and 6 months. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an accelerated dosing schedule for Twinrix consisting of 3 doses given on days 0, 7, and 21-30 days, followed by a booster dose at 12 months. This accelerated regimen should be considered for departures occurring in less than 6 months where hepatitis B protection is needed.

Vivaxim is usually given as a single dose and the hepatitis A component boosted 6-12 months later. However, a single dose may confer up to 3 years of protection against hepatitis A and typhoid.

Children should be immunised against hepatitis A after 12 months of age. Unfortunately the vaccine is not currently provided as part of the Australian Immunisation Schedule and vaccines must be purchased. Its introduction to the paediatric schedule in the USA (12-23 months) has been advised by the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) and is considered cost effective in that country.

Indications for vaccine

Australians most in need of vaccination against hepatitis A are international travellers, children living in remote areas, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men. Hepatitis A vaccination is recommended for persons with an increased risk of acquiring hepatitis A and/or who are at increased risk of severe disease. Serological testing for immunity to hepatitis A from previous infection is not usually required prior to vaccination, but may be indicated in some circumstances.

The use of hepatitis A vaccine is preferred over immune globulin for post-exposure prophylaxis in healthy persons between 2 and 40 years.

There is no specific treatment for hepatitis A.

History

Hepatitis A is one of the oldest diseases known to mankind. The HA virus was first discovered in 1973 by Steven M. Feinstone at the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, as a nonenvoloped, spherical, positive stranded RNA virus. The first descriptions of hepatitis (epidemic jaundice) are generally attributed to Hippocrates. Outbreaks of jaundice, probably hepatitis A, were reported in the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly in association with military campaigns. Hepatitis A was first differentiated epidemiologically from hepatitis B in the 1940s. Development of serologic tests allowed definitive diagnosis of hepatitis B. In the 1970s, identification of the virus, and development of serologic tests helped differentiate hepatitis A from other types of non-B hepatitis.

The future

Epaxal is a new hepatitis A vaccine and is the first to utilise virosome technology, in which the hepatitis A virion and influenza antigens are combined with liposomes. Early trials suggest rapid and prolonged effectiveness.