The Disease

Cholera results from infestation by the cholera bacteria (Vibrio cholerae), serogroups 01 and 0139. It is usually acquired from food or water contaminated by human faeces or vomitus. Although not common in travellers, cholera is a potentially serious disease. It is a low risk for most travellers; however, vaccination should always be discussed with your travel doctor.

The term non-Vibrio cholera (NVC) refers to cases of cholera-like illness caused by organisms other than the 01 or 0139 Vibrio species.

The incubation period is from a few hours to a few days.

Epidemiology

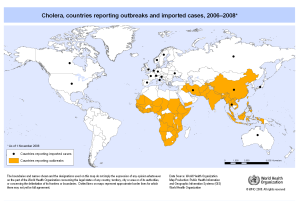

The disease is usually transmitted via food and water contaminated with human excreta. Seafood such as shellfish obtained from contaminated waters have also been responsible for outbreaks. Cholera is a substantial health burden in developing countries and is considered to be endemic in Africa, Asia, South America and Central America.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is confirmed by the isolation of V.cholerae serogroup O1 or O139 from faeces.

Features

In mild cases, diarrhoea is the only symptom. In severe cases, profuse watery (rice water) diarrhoea, with nausea and vomiting leads to rapid dehydration and, if untreated, death may occur within a few hours in a half of untreated cases.

Cholera occurs mainly in poor countries with inadequate sanitation and lack of clean drinking water. Up to 6 cases occur each year in Australia, almost all in individuals infected while travelling abroad.

Outbreaks of cholera causing deaths are constantly reported from three continents. The disease appears to be increasing worldwide in both the number of cases and in their distribution.

Travellers

The risk is very low for travellers, even in countries where cholera epidemics occur. Humanitarian relief workers in disaster areas and refugee camps are at risk.

Travellers to sub-Saharan Africa are advised to check the Smartraveller web site. The oral vaccine Dukarol is not available in the Unites States and alternative control measures are spelt out in the CDC information page.

Travellers should take great care with food and water quality (as advised by your GoodTrips doctor) and carry oral rehydration salts in case of severe diarrhoea.

Vaccine Information.

The vaccine available in Australia is given orally:

Dukarol is a heat-killed preparation, containing several strains of a Vibrio cholerae, is given in two doses (more than a week apart) and protects against diarrhoea caused by Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC). ETEC, which generally results in milder disease, is one of the most common causes of infectious diarrhoea, and the single most common cause of travellers diarrhoea.

Cholera vaccine is not routinely recommended for travellers but, where risk of infection is high, booster doses are advised at six monthly intervals. It is not available in the US. WHO no longer recommends the injectable cholera vaccine.

Australian Immunisation Handbook:

There is structural similarity and immunologic cross-reactivity between the cholera toxin and the heat-labile toxin of E. coli, which is often associated with ‘travellers’ diarrhoea’. Therefore, it had been suggested that the rCTB-containing vaccine may also provide protection against heat-labile toxin producing enterotoxigenic E. coli (LT-ETEC).

Dukoral is, by contrast to earlier cholera vaccines, very effective for at least two years.

Dosing

Adults and children (> 6 years)

Two doses are required, given a minimum of 1 week and up to 6 weeks apart. If the 2nd dose is not administered within 6 weeks, re-start the vaccination course.

Dukoral is administered orally. After dissolving the buffer granules in 150 mL of water, the contents of the vaccine vial are then added to the solution for administration.

Children (2 – 6 years)

Three doses are required, given a minimum of 1 week and up to 6 weeks apart. If an interval of more than 6 weeks occurs between any of the doses, re-start the vaccination course.

Dukoral is not registered for use in children aged <2 years and is not recommended for use in this age group.

Co-administration with other vaccines

The inactivated oral cholera vaccine can be given with, or at any time before or after, other travel vaccines, such as yellow fever or parenteral Vi polysaccharide typhoid vaccines.

However, there should be an interval of at least 8 hours between the administration of the inactivated oral cholera vaccine and oral live attenuated typhoid vaccine (Vivotif).

Recommendations

Cholera vaccination should be considered for travellers at increased risk of acquiring diarrhoeal disease, such as those with achlorhydria, and for travellers at increased risk of severe or complicated diarrhoeal disease, such as those with poorly controlled or otherwise complicated diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, HIV/AIDS or other conditions resulting in immunocompromise, or significant cardiovascular disease.

Cholera vaccination should also be considered for travellers with considerable risk of exposure to, or acquiring, cholera, such as humanitarian disaster workers deployed to regions with endemic or epidemic cholera.

Stockpile

In 2011, the World Health Assembly called for the implementation of an integrated comprehensive approach to cholera control that might include the use of cholera vaccines “where appropriate.” In 2012, a WHO working group recommended establishing a stockpile of 2 million doses of vaccine to be held at the manufacturers’ sites, building up to 6 million doses over 3 years, and adopting the ICG model of governance. As of September 2014, 1.5 million doses had been distributed.

History

Cholera has been described over the past two centuries and probably had its origins in the Ganges delta in India.

The bacterium was isolated in 1854 by Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini, but its exact nature and his results were not widely known.

Vaccines were first developed by Jaume Ferran i Clua (1885) and by Waldemar Haffkine (1892). In 1959, Dr Sambhu Nath De (Dr S N De) discovered the enterotoxin secreted by the cholera bacteria, thus leading to the development of vaccines against the enterotoxin, rather than against the bacteria.

In the Australian colonies, cholera or diarrhoeal diseases described as such, made sporadic appearances. In India in 1817, cholera became “extremely active” and several pandemics, involving SE Asia and Europe, occurred. Remarkably, Australia experienced minimal disease burden despite the large numbers of Chinese arrivals after the discovery of gold in 1850.

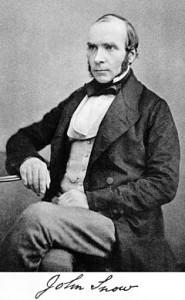

John Snow (1813-1858) was a brilliant doctor living in London at the time of a serious outbreak of cholera.

His study of cholera cases and their geographical relationship to a hand pump in Broad Street was the beginning of the science of epidemiology. Despite the reluctance of authorities to believe the connection between faeces and cholera, which Snow suggested, his endeavours led to improvements in public health especially in regard to clean water, around the world.

Cholera is a ‘quarantinable disease under the Commonwealth Quarantine Act and is a notifiable disease in each state.