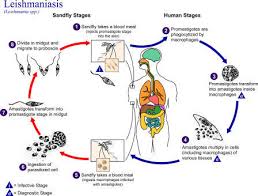

Leishmaniasis is a group of diseases caused by the protozoan parasite Leishmania of which there are about 20 species. They are transmitted to humans through the bites of female phlebotomine sandflies, which are found in forested areas, caves or the burrows of small rodents. It has been reported from 98 countries, but is not contagious.

Some 70 animal species, including humans, have been found as natural reservoir hosts of Leishmania parasites.

After malaria, visceral leishmaniasis is the largest parasitic killer in the world. Leishmaniasis is categorised geographically as “New World” (Central and South America, and Texas in the United States) or “Old World” (the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East and Africa). Lutzomyia is the sandfly vector in the New World and Phlebotomus in the Old World.

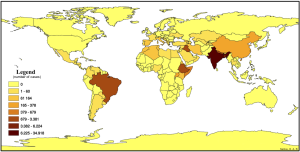

WHO estimates that the disease results in 2 million new cases a year, threatens 350 million people in 88 countries and that there are 12 million people currently infected worldwide.

It is classified as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD).

Distribution

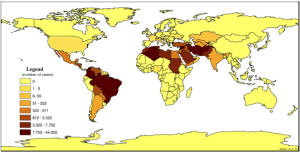

The disease mainly affects poor people in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and is associated with malnutrition, population displacement, poor housing, weak immune system and lack of resources. (Leishmaniasis was previously thought to not exist in Australia [and Oceania] until 2003 when a new species was discovered in kangaroos and wallaroos in the Northern Territory and carried by day-feeding midges – not phlebotomine sandflies.)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the more common form of the disease and is more widely distributed, with about one-third of cases occurring in each of three epidemiological regions, the Americas, the Mediterranean basin, and western Asia from the Middle East to Central Asia. The ten countries with the highest estimated case counts are: Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Iran, Peru, Sudan and Syria, and together account for 70 to 75% of global estimated CL incidence.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) is found mainly in South America (mainly Brazil, Bolivia and Peru).

More than 90% of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) cases occur in six countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan and Sudan.

Frequency

For CL, estimates of the number of cases range from approximately 0.7 – 1.2 million. For VL, estimates of the number of cases range from approximately 0.2 – 0.4 million.

Clinical features

There are three main forms of the disease:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis

Some people have no symptoms or signs of disease, but in all three forms, the infection may be severe.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) Most commonly skin sores, which may start as lumps or bumps, appear several weeks after the bite of a sand fly. The lumps may become ulcers with a central crater and raised edges and may be covered by a scab or crust. They are usually painless but can become painful with secondary infection. Quite commonly, more than one lesion is seen.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL)

The pathogenesis of MCL is unclear but develops in a similar manner to CL – and the two forms may coexist. MCL occurs when cutaneous lesions expand to the mucosal region or through metastasis and it is not uncommon for MCL to develop many years after the recovery of an initial lesion. The result is a gradual and progressive development of destructive lesions causing erosion and disfigurement of the nose, mouth and throat – but not of bone.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL)

VL is also known as kala-azar, black fever or Dumdum fever; it is the most severe form of leishmaniasis. The clinical features of VL caused by different species are different, and each parasite has a unique epidemiological pattern.

Typically, those affected have a fever, weight loss and enlargement of the spleen and liver, anaemia, pancytopaenia and hypergammaglobulinaemia. These symptoms may be confused with those of malaria. In some areas, the skin is very dark and opportunistic infections such as pneumonia, TB, AIDS and dysentery, may lead to death.

After recovery, some patients (50% in Sudan and 1 – 3% in India) develop post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL), which requires prolonged and expensive treatment.

Treatment

Vaccination

No vaccines are currently in use, although several are under development.

The genome of the parasite L. major has been sequenced, allowing for the identification of proteins used by the pathogen but not by humans.

Vector control

Management is based on the control of the sandfly vector and rodent reservoirs.

Visceral leishmaniasis has a rapid course in HIV-infected patients, who require specialised care.

Drug treatment

Visceral disease

For many years, the treatment of leishmaniasis was based on a six-day course of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam GSK), an organic pentavalent antimony compound. Developing resistance, phlebotoxicity and other side effects has limited its use.

The oral agent, miltefosine (Impavido Paladin Therapeutics), is a phospholipid with antineoplastic qualities was developed in the late 1980s and is the first (and only) oral FDA-approved drug for the treatment of both visceral and cutaneous disease.

Cutaneous diseases

The evidence around the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is poor.

Fluconazole treatment for 6 weeks speeds up the already-rapid cure rate of cutaneous disease due to Leishmania major.