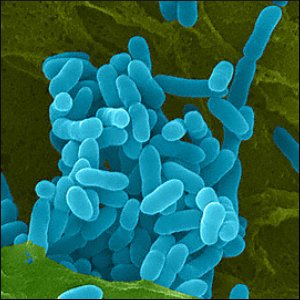

Melioidosis is caused by the Gram negative bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei, found in soil, stagnant water and rice paddies. It is endemic in parts of South East Asia (especially Thailand), Taiwan and northern Australia and occurs sporadically in South America, the Middle East and several African countries.

Synonyms: Nightcliff gardener’s disease, Darwin disease, Whitmore’s disease, paddy field disease, pseudoglanders.

The Disease

Epidemiology

Transmission occurs through contact with damaged skin, inhaled dust or ingestion of contaminated water. Inhaled organisms rapidly travel to the brain and spinal cord.

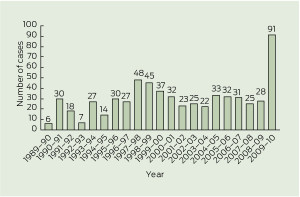

The majority of cases are associated with the wet season and exposure to surface water and mud, implying that acute infection most commonly occurs soon after exposure.

People with occupational or recreational exposure to moist soil or surface water are at greatest risk. These include rice farmers, other agricultural workers, building site labourers, adventure travellers, soldiers and a variety of indigenous groups.

Case clusters have been described following flooding and cyclones and probably relate to exposure. Most cases in northern Australia occur during the wet season.

Comorbidities (including diabetes, chronic renal failure, high alcohol consumption, malignancy) are strongly associated with severe infection and poor outcomes.

The incubation period is about 9 days, but ranges from 1 to 21 days.

Notification should be made to the relevant state authorities in Australia.

Features

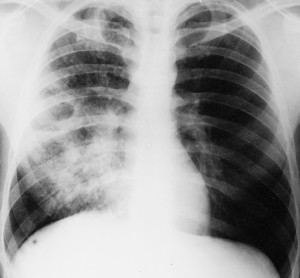

The disease may range from asymptomatic to rapidly fulminant and show regional variations in presentation. Fever and pneumonia are the most common presenting symptoms. Asymptomatic septicaemia may produce a rapidly fatal illness with cough, chest pain and haemoptysis or occur years after the initial exposure. Abdominal abscess formation may occur and an encephalomyelitis syndrome is recognised in northern Australia.

Chronic melioidosis (> 2 months) occurs in approximately 10% of patients and may present as chronic skin infection, skin ulcers and lung nodules or chronic pneumonia, closely mimicking tuberculosis or pericarditis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by culture from any clinical sample, which should include samples of blood, sputum, urine and throat swabs.

Serology – indirect haemagglutination assay (IHA).

Prevention

No vaccines available.

Avoid exposure to soil and rice paddies in endemic areas, especially if immunocompromised or diabetic and especially in the presence of open wounds.

Treatment

1. Intravenous intensive phase – 3rd generation cephalosporins or meropenem or amoxicillin-clavulanate for 10-14 days.

2. Eradication phase – co-trimoxazole and doxycycline for 12 to 20 weeks.

Mortality:

90% without treatment

50% with treatment

Travellers

Travellers using Goodrips Travel resources will be provided with information from Travax Encompass for the following risk countries: Australia, Thailand, Singapore, Cambodia, Malaysia, Taiwan, Laos, India, Brunei, China, and Hong Kong; statements have also been added for the following lower-risk countries: Honduras, Mexico, Aruba, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Puerto Rico, Brazil, Colombia, Madagascar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Burma, Philippines, Vietnam, New Caledonia, and Papua New Guinea.

Travellers engaged in hiking, biking, swimming, or other outdoor activities are advised to wear proper footwear and avoid direct contact with potentially contaminated water or soil.

Animals affected by melioidosis

Severely – sheep, goats, pigs.

Occasionally – cattle, horses, dogs, cats, rodents, monkeys, birds

Melioidosis has a resemblance to glanders, a zoonotic disease of horses.

History

From GlobalSecurity.org:

Captain Alfred Whitmore (1876–1946), a British pathologist serving in Burma, and his assistant C.S. Krishnaswami, first described septicaemic melioidosis in 1911-1912. The bacteria were isolated from morphine addicts in Rangoon, Burma.

During the French occupation of Vietnam between 1948 and 1954, over 100 cases of melioidosis were diagnosed. During the American occupation, over 300 cases were diagnosed. Soldiers acquired the disease by directly exposing wounds to soil or water carrying the Burkholderia pseudomallei bacteria or through inhalation. Melioidosis was known as the “Vietnamese Time Bomb” due to its potentially long incubation period; soldiers experience symptoms long after their return home. The longest documented period of latency was 26 years.

The United States and Soviet Union biological weapons programs both studied melioidosis as a possible biological weapons agent.